I suppose one should feel some sympathy for Mel Gibson, who'd apparently been off the booze for a long time before very spectacularly getting back on it, but nah. Not when he's operating a car and endangering other people's lives. Not to mention when he spouts anti-Semitic garbage once he's arrested. Not to mention his very ungallant remarks to a female police officer. (William Wallace would never have treated Princess Isabella like that.)

A pity the historical accuracy police weren't on patrol that night also.

Medieval History, and Tudors Too!

Monday, July 31, 2006

Saturday, July 29, 2006

Richard III's Mother-in-Law, and My Five Favorite Historical Novels

Maybe you've been like the guy below, saying to yourself, "Gee, I wish I knew more about Richard III's mother-in-law, Anne Beauchamp, Countess of Warwick. I wonder where I could find out more about her." (Admit it. Of course you've been thinking this. It's been tearing at you this entire summer.) Well, ponder no more, but venture over here in my website, where you'll find a nice long piece about the countess. You can also find a piece about everyone's favorite bareback rider, Lady Godiva, written by novelist Octavia Randolph, and about everyone's favorite extortionist, Hugh le Despenser the younger, written by Alianore. (And since Hugh was also a pirate, you can get your summer pirate fix without even having to pay for movie admission and popcorn.)

Anyway, Carla posted about her five favorite historical novels, and invited others to join in. So here are my five, with the caveat that I tend to read only about people and time periods I'm interested in and therefore have undoubtedly missed some of the greats. (And though I've made a selection, it's not set in stone, or bronze for that matter; next week I could have five different choices.)

1. A Tale of Two Cities. This and Barnaby Rudge (which is hard going even for many Dickensians like myself) were Dickens's two ventures into historical fiction. Yes, there are some cloying bits, but you gotta admire a guy who goes to the scaffold all for the sake of the woman he loves.

2. Gone with the Wind. Granted, some of the racial stereotypes are cringe-inducing today, but this novel by Margaret Mitchell has two of the most memorable romantic leads ever created, and the other characters are equally compelling, as is the plot. (And though my ancestors fought for the South, I'm quite happy that the North won, so this isn't the view of a diehard Confederate.)

3. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. I read this Betty Smith novel during the same summer I read Gone With the Wind, right after eighth grade, and I count these two books as my first real venture into adult reading. I'm not sure this strictly counts as a historical novel--it was written in the 1940's and is set in the early part of the century. Still, it's a wonderful story of a young girl growing up in turn-of-the-century Brooklyn, and as America changed a great deal between the time in which it was set and in the time in which it was written, I'm going to count it as historical fiction. So there.

4. Sharon's Penman's trilogy of Here Be Dragons, Falls the Shadow, and The Reckoning. Some authors can take real historical characters and make them as dull as dirt--an amazing feat when you think of it. Penman's characters, on the other hand, are fully rounded, so much so that I find a few of them, like Joanna in Here Be Dragons, to be downright exasperating. That's a compliment; one gets bored with cardboard cutouts, but never exasperated.

5. Sandra Gulland's Josephine Bonaparte trilogy. It's difficult for an author to make the journal form work, but Gulland does. Josephine is a compelling heroine without being a politically correct "strong woman," and the book is lit up by a nice sense of humor.

Others I've really liked? Margaret George's The Autobiography of Henry VIII, Jean Plaidy's Murder Most Royal and The Queen's Confession, Brenda Honeyman's The Queen and Mortimer, Pamela Bennetts' The She-Wolf, and Reay Tannahill's The Seventh Son. Just to name a few.

(Oh, and I liked The Traitor's Wife: A Novel of the Reign of Edward II also, by good ol' whatsername.)

Anyway, Carla posted about her five favorite historical novels, and invited others to join in. So here are my five, with the caveat that I tend to read only about people and time periods I'm interested in and therefore have undoubtedly missed some of the greats. (And though I've made a selection, it's not set in stone, or bronze for that matter; next week I could have five different choices.)

1. A Tale of Two Cities. This and Barnaby Rudge (which is hard going even for many Dickensians like myself) were Dickens's two ventures into historical fiction. Yes, there are some cloying bits, but you gotta admire a guy who goes to the scaffold all for the sake of the woman he loves.

2. Gone with the Wind. Granted, some of the racial stereotypes are cringe-inducing today, but this novel by Margaret Mitchell has two of the most memorable romantic leads ever created, and the other characters are equally compelling, as is the plot. (And though my ancestors fought for the South, I'm quite happy that the North won, so this isn't the view of a diehard Confederate.)

3. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. I read this Betty Smith novel during the same summer I read Gone With the Wind, right after eighth grade, and I count these two books as my first real venture into adult reading. I'm not sure this strictly counts as a historical novel--it was written in the 1940's and is set in the early part of the century. Still, it's a wonderful story of a young girl growing up in turn-of-the-century Brooklyn, and as America changed a great deal between the time in which it was set and in the time in which it was written, I'm going to count it as historical fiction. So there.

4. Sharon's Penman's trilogy of Here Be Dragons, Falls the Shadow, and The Reckoning. Some authors can take real historical characters and make them as dull as dirt--an amazing feat when you think of it. Penman's characters, on the other hand, are fully rounded, so much so that I find a few of them, like Joanna in Here Be Dragons, to be downright exasperating. That's a compliment; one gets bored with cardboard cutouts, but never exasperated.

5. Sandra Gulland's Josephine Bonaparte trilogy. It's difficult for an author to make the journal form work, but Gulland does. Josephine is a compelling heroine without being a politically correct "strong woman," and the book is lit up by a nice sense of humor.

Others I've really liked? Margaret George's The Autobiography of Henry VIII, Jean Plaidy's Murder Most Royal and The Queen's Confession, Brenda Honeyman's The Queen and Mortimer, Pamela Bennetts' The She-Wolf, and Reay Tannahill's The Seventh Son. Just to name a few.

(Oh, and I liked The Traitor's Wife: A Novel of the Reign of Edward II also, by good ol' whatsername.)

Monday, July 24, 2006

Bag Full o' Books, and a Mixed Bag at That

Partly for fun, and partly in the noble cause of providing some fodder for the Medieval Miniatures section of my website, I've been reading some nonfiction lately. Here are a few interesting things I've checked out from the library:

Hazel Pierce, Margaret Pole: Countess of Salisbury 1473-1541. A well-researched account of the daughter of George, Duke of Clarence, who survived Richard III's reign and Henry VII's reign, only to be executed by Henry VIII when she was well into her sixties.

Anne F. Sutton & Livia Visser-Fuchs, Richard III's Books: Ideals and Reality in the Life and Library of a Medieval Prince. Much more, as you can tell from the subtitle, than a simple inventory of books found in the king's library.

Wendy Childs, editor, Vita Edwardi Secvndi: The Life of Edward the Second. A nice new edition of a chronicle written by an unknown contemporary of Edward II.

A. J. Pollard, Richard III and the Princes in the Tower. One of the most readable Richard III studies I've seen, and one that neither romanticizes nor demonizes the controversial king.

All of these books can come to my shelf and sit anytime they want.

I'm also reading Joanna Denny's 2005 biography, Katherine Howard: A Tudor Conspiracy. Unfortunately, I can't put this book in the same category as the ones above. Denny states as undisputed fact that Henry VIII was the father of Mary Boleyn's children, when the prevailing opinion seems to be that Mary conceived them with her husband after the royal affair had ended, and she suggests, based on very shaky evidence, that Henry VIII had his own out-of-wedlock son, Henry Fitzroy, poisoned. She credits Henry VIII with having executed over 50,000 people (p. 133), a number that strikes me as incredibly high.

Since Katherine's short life and even shorter reign are notable mostly for her sexual conduct, Denny understandably spends a lot of time on sexual mores. While it's commendable that Denny recognizes that much of the behavior that would bring Katherine to the scaffold occurred at an age when she was easily led and vulnerable, Denny's discussion veers toward the ridiculous. She spends too much time on generalizations such as "sex was hurriedly performed in darkness" (p. 84--was there a fifteenth-century version of Masters and Johnson surveying couples?) and on overdramatics such as "her innocence had been traded for food and lodging from the age of seven thanks to a wastrel father and a callous family" (p. 194). She discusses at some length the custom of "bundling," stating that it was "an accepted part of 17th-century courting rituals" (p. 83) and even incorrectly citing Romeo and Juliet's postmarital night together as an example (p. 83, 87), but she never explains how this custom relates to Katherine, who by her own admission went much further than bundling in her relationship with Francis Dereham.

Denny eschews footnotes in favor of a listing of sources for each chapter. Unfortunately, this system is fairly useless for someone wanting to know a source for a specific statement, such as the 50,000-executions figure mentioned above.

In short, I found this a biography that offered more frustration than information. As there has been relatively little nonfiction written about Katherine Howard, though, those interested in Henry VIII's wives might find it worth their while to get a library copy.

Hazel Pierce, Margaret Pole: Countess of Salisbury 1473-1541. A well-researched account of the daughter of George, Duke of Clarence, who survived Richard III's reign and Henry VII's reign, only to be executed by Henry VIII when she was well into her sixties.

Anne F. Sutton & Livia Visser-Fuchs, Richard III's Books: Ideals and Reality in the Life and Library of a Medieval Prince. Much more, as you can tell from the subtitle, than a simple inventory of books found in the king's library.

Wendy Childs, editor, Vita Edwardi Secvndi: The Life of Edward the Second. A nice new edition of a chronicle written by an unknown contemporary of Edward II.

A. J. Pollard, Richard III and the Princes in the Tower. One of the most readable Richard III studies I've seen, and one that neither romanticizes nor demonizes the controversial king.

All of these books can come to my shelf and sit anytime they want.

I'm also reading Joanna Denny's 2005 biography, Katherine Howard: A Tudor Conspiracy. Unfortunately, I can't put this book in the same category as the ones above. Denny states as undisputed fact that Henry VIII was the father of Mary Boleyn's children, when the prevailing opinion seems to be that Mary conceived them with her husband after the royal affair had ended, and she suggests, based on very shaky evidence, that Henry VIII had his own out-of-wedlock son, Henry Fitzroy, poisoned. She credits Henry VIII with having executed over 50,000 people (p. 133), a number that strikes me as incredibly high.

Since Katherine's short life and even shorter reign are notable mostly for her sexual conduct, Denny understandably spends a lot of time on sexual mores. While it's commendable that Denny recognizes that much of the behavior that would bring Katherine to the scaffold occurred at an age when she was easily led and vulnerable, Denny's discussion veers toward the ridiculous. She spends too much time on generalizations such as "sex was hurriedly performed in darkness" (p. 84--was there a fifteenth-century version of Masters and Johnson surveying couples?) and on overdramatics such as "her innocence had been traded for food and lodging from the age of seven thanks to a wastrel father and a callous family" (p. 194). She discusses at some length the custom of "bundling," stating that it was "an accepted part of 17th-century courting rituals" (p. 83) and even incorrectly citing Romeo and Juliet's postmarital night together as an example (p. 83, 87), but she never explains how this custom relates to Katherine, who by her own admission went much further than bundling in her relationship with Francis Dereham.

Denny eschews footnotes in favor of a listing of sources for each chapter. Unfortunately, this system is fairly useless for someone wanting to know a source for a specific statement, such as the 50,000-executions figure mentioned above.

In short, I found this a biography that offered more frustration than information. As there has been relatively little nonfiction written about Katherine Howard, though, those interested in Henry VIII's wives might find it worth their while to get a library copy.

Friday, July 21, 2006

Alison Weir's novel, and Hamlet on the Highway

I finished Alison Weir's first historical novel, Innocent Traitor, today. This is Weir's take on the story of Lady Jane Grey, the "Nine Days' Queen." The story spans the time from Jane's birth, when she sorely disappoints her parents by not being a boy, to her death.

Weir chose an interesting narrative style for her novel. Instead of the time-honored (and very shopworn) "let me look back upon my life upon the eve of my death" first-person narration, she tells Jane's story through a variety of first-person narrators: Jane, Jane's nurse, Jane's mother, Queen Jane Seymour, Queen Katherine Parr, Queen Mary, John Dudley, and, finally, Jane's executioner. Several people who have read the book have commented that they disliked the jumps from narrator to narrator. I didn't find this bothersome, as it allows the reader to know things that Jane could not have known and to witness events she could not have witnessed; it also allows Weir to give necessary background information without sounding strained and artificial. Futhermore, the device of the multiple narrators enables Weir to make points without beating them in: for instance, we can see, as Jane and Mary can't, how much in common the rigidly Catholic Mary has with the rigidly Protestant Jane. (Sometimes, too, the multiple narrators add some comparatively light relief in what's mostly a rather dark novel, as when we discover what Queen Katherine Parr really thinks of Jane's mother.)

My only objection to the narrators, in fact, was that men were underrepresented. The only man we hear from regularly, John Dudley, is a thoroughgoing villain; though his perspective was a useful one, it would have added more balance to the book to hear from others as well, preferably more complex, conflicted men than he. I especially felt the absence of not knowing what Jane's father was thinking--or not thinking--when he laid his final, unsuccessful plot. I would have also liked to hear more from Jane's callow husband.

Jane and her family are handled well. Jane's parents treat her shabbily and insensitively, yet Weir manages to convey all of their considerable flaws without making them completely hateful. (Jane's mother Frances, genuinely grieved over her daughter's impending death yet still able to arrange to console herself with her young master of horse, is especially memorable.) Jane herself is a well-rounded character: strong-willed and good-hearted, yet with a self-righteous, almost irritating streak that saves her from being simply a pathetic victim.

All in all, I finished this novel feeling a genuine sense of loss, and I'm looking forward to Weir's next excursion into historical fiction.

Next on my reading list: an excursion to the lighter side of life with An Assembly Such as This, a Pride and Prejudice fan fiction from Darcy's point of view. Nary a chopped head to be found in this one, I trust.

By the way, when driving today, I noticed that the car in front of me had license plates reading 2BRNT2B. I presume Hamlet's failure to use his turn signals was a symptom of his famed inability to make up his mind, but I'm not sure what would explain his speeding. Perhaps his distress over the state of Denmark. Or maybe the funeral baked meats didn't agree with his digestion. Anyway, slow down, dude. The readiness is all.

Weir chose an interesting narrative style for her novel. Instead of the time-honored (and very shopworn) "let me look back upon my life upon the eve of my death" first-person narration, she tells Jane's story through a variety of first-person narrators: Jane, Jane's nurse, Jane's mother, Queen Jane Seymour, Queen Katherine Parr, Queen Mary, John Dudley, and, finally, Jane's executioner. Several people who have read the book have commented that they disliked the jumps from narrator to narrator. I didn't find this bothersome, as it allows the reader to know things that Jane could not have known and to witness events she could not have witnessed; it also allows Weir to give necessary background information without sounding strained and artificial. Futhermore, the device of the multiple narrators enables Weir to make points without beating them in: for instance, we can see, as Jane and Mary can't, how much in common the rigidly Catholic Mary has with the rigidly Protestant Jane. (Sometimes, too, the multiple narrators add some comparatively light relief in what's mostly a rather dark novel, as when we discover what Queen Katherine Parr really thinks of Jane's mother.)

My only objection to the narrators, in fact, was that men were underrepresented. The only man we hear from regularly, John Dudley, is a thoroughgoing villain; though his perspective was a useful one, it would have added more balance to the book to hear from others as well, preferably more complex, conflicted men than he. I especially felt the absence of not knowing what Jane's father was thinking--or not thinking--when he laid his final, unsuccessful plot. I would have also liked to hear more from Jane's callow husband.

Jane and her family are handled well. Jane's parents treat her shabbily and insensitively, yet Weir manages to convey all of their considerable flaws without making them completely hateful. (Jane's mother Frances, genuinely grieved over her daughter's impending death yet still able to arrange to console herself with her young master of horse, is especially memorable.) Jane herself is a well-rounded character: strong-willed and good-hearted, yet with a self-righteous, almost irritating streak that saves her from being simply a pathetic victim.

All in all, I finished this novel feeling a genuine sense of loss, and I'm looking forward to Weir's next excursion into historical fiction.

Next on my reading list: an excursion to the lighter side of life with An Assembly Such as This, a Pride and Prejudice fan fiction from Darcy's point of view. Nary a chopped head to be found in this one, I trust.

By the way, when driving today, I noticed that the car in front of me had license plates reading 2BRNT2B. I presume Hamlet's failure to use his turn signals was a symptom of his famed inability to make up his mind, but I'm not sure what would explain his speeding. Perhaps his distress over the state of Denmark. Or maybe the funeral baked meats didn't agree with his digestion. Anyway, slow down, dude. The readiness is all.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Mickey Spillane Does the Wars of the Roses

When you’ve been reading the Mickey Spillane obits, and you’ve been researching the Wars of the Roses, and it’s late at night, and you haven’t updated your blog in a few days, this is what happens. Really.

The future Edward IV to Eleanor Talbot

(—Black Alley)

Edward IV to George, Duke of Clarence

(—Vengeance Is Mine)

Buckingham to the future Richard III

(—I, the Jury)

Richard III before the Battle of Bosworth

(—One Lonely Night)

(For the excerpts on which these are based, see The Unofficial Mickey Spillane Mike Hammer Site by David Seong. Tell him Suzie sent you.)

(On a totally unrelated subject, it was a pleasure to see this today.)

The future Edward IV to Eleanor Talbot

"It isn't going to be easy getting through this engagement, kitten, but let's keep it cool until we do."

(—Black Alley)

Edward IV to George, Duke of Clarence

I said, "George, you've forgotten something. You've forgotten that I'm not a guy that takes any crap. Not from anybody. You've forgotten I've been king because I stayed alive longer than some guys who didn't want me that way. You've forgotten that I've had some punks tougher than you'll ever be on the end of a sword and I stabbed them just to watch their expressions change."

He was scared, but he tried to bluff it out anyway. He said, "Why don'tcha try it now, Eddie?"

(—Vengeance Is Mine)

Buckingham to the future Richard III

“You can figure things out as quickly as I can, but you haven't got the ways and means of doing the dirty work. That's where I come in. You'll be right behind me every inch of the way, but when the pinch comes I'll get shoved aside and you slap the crown on."

(—I, the Jury)

Richard III before the Battle of Bosworth

I used to be able to look at myself and grin without giving a damn about how ugly it made me look. Now I was looking at myself the same way those people did back there. I was looking at a hunchbacked guy with an ugly reputation, a guy who had no earthly reason for existing in a decent, normal society. That's what the chroniclers had said. . . .

I was a killer. I was a murderer, legalized. I had no reason for living.

(—One Lonely Night)

(For the excerpts on which these are based, see The Unofficial Mickey Spillane Mike Hammer Site by David Seong. Tell him Suzie sent you.)

(On a totally unrelated subject, it was a pleasure to see this today.)

Sunday, July 16, 2006

Girls, Girls, Grammar

It's been at least two months since I've been to the beach, a long overdue trip. So I was pleased to go there this weekend. (While there, I finished reading a big fat historical novel, but I can't blog about it because I'm reviewing it for the Historical Novel Society.)

Part of the fun of going to the beach is reading the signs in the small towns we pass through to get there. For some time, one of my favorites has been this hand-lettered one: "Boil Peanuts. Circle Drive." Unfortunately, we can never follow this command, since we don't carry the implements necessary to boil peanuts, which it seems is a prerequisite to circling the drive, wherever that might be.

As our trip to the beach takes us through a military town, strip clubs are in abundance, and my very favorite sign used to be that of a club that offered wrestling in various types of substances, changing weekly. Sometimes the substances even had a seasonal theme: during Thanksgiving, for example, cranberry sauce was the ingredient of choice. About a year ago, however, the signs stopped advertising wrestling, presumably either because the club proprietors ran out of ideas for new substances or because the city officials decided that the public health was at stake. After that, the sign settled down to the dull and seldom changing "Girls, Girls, Girls!"

This weekend was no different, except that in addition to advertising girls, girls, and girls, the club added "Good Times Everyday" to its sign. Had I possessed a stepladder, and were I not afraid of being mistaken for one of the "Girls, Girls, Girls," I could have moved the magnetic letters over just a fraction, enough to transform "Good Times Everyday" into "Good Times Every Day." That task being completed, I could have driven to the beach with a lighter heart. Alas, I could not, and had to console myself with writing this blog entry upon my return in the feeble hope that the club owners see it and mend their ways.

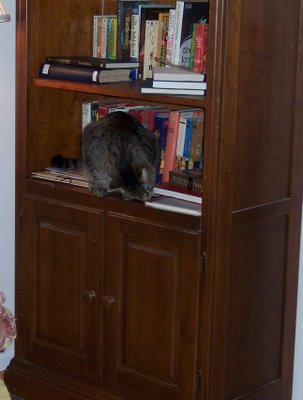

So, this post is void of historical fiction content, you're thinking? No, indeed! Why, here's Onslow the cat playing amongst the historical fiction. You'll note that he's next to a group of Sharon Penman and Jean Plaidy novels and is investigating Paul Murray Kendall's biography of Richard III. But whether Onslow likes his roses red or white is a mystery to me, and most likely will remain that way.

Part of the fun of going to the beach is reading the signs in the small towns we pass through to get there. For some time, one of my favorites has been this hand-lettered one: "Boil Peanuts. Circle Drive." Unfortunately, we can never follow this command, since we don't carry the implements necessary to boil peanuts, which it seems is a prerequisite to circling the drive, wherever that might be.

As our trip to the beach takes us through a military town, strip clubs are in abundance, and my very favorite sign used to be that of a club that offered wrestling in various types of substances, changing weekly. Sometimes the substances even had a seasonal theme: during Thanksgiving, for example, cranberry sauce was the ingredient of choice. About a year ago, however, the signs stopped advertising wrestling, presumably either because the club proprietors ran out of ideas for new substances or because the city officials decided that the public health was at stake. After that, the sign settled down to the dull and seldom changing "Girls, Girls, Girls!"

This weekend was no different, except that in addition to advertising girls, girls, and girls, the club added "Good Times Everyday" to its sign. Had I possessed a stepladder, and were I not afraid of being mistaken for one of the "Girls, Girls, Girls," I could have moved the magnetic letters over just a fraction, enough to transform "Good Times Everyday" into "Good Times Every Day." That task being completed, I could have driven to the beach with a lighter heart. Alas, I could not, and had to console myself with writing this blog entry upon my return in the feeble hope that the club owners see it and mend their ways.

So, this post is void of historical fiction content, you're thinking? No, indeed! Why, here's Onslow the cat playing amongst the historical fiction. You'll note that he's next to a group of Sharon Penman and Jean Plaidy novels and is investigating Paul Murray Kendall's biography of Richard III. But whether Onslow likes his roses red or white is a mystery to me, and most likely will remain that way.

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

If They Loved It Once, They'll Love It Again

I once was on a list where one writer threw a hissy fit that another writer on the list was using “her” title for a novel in a very different genre and with an entirely different target audience. (Oddly, neither writer appeared to realize that the title both were using had been used years before by a well-known novelist and that the novel in question was still a top seller on Amazon.)

It’s a good thing neither of these writers was publishing historical fiction, where some titles are so good that they keep popping up again and again, both within and without the genre. Mind you, I’m not suggesting that this is at all illegal or unethical—my own novel, in fact, shares a moniker with at least two older books, one a 1908 novel long out of print, the other a 1960’s novel out of print but still easily had on the secondhand market. Perhaps, however, it’s time to retire some of the titles below, just like the jerseys of football and basketball greats:

The Court(s) of Love. Used by Jean Plaidy, Denee Cody, Peter Bourne, Alice Brown, and Ellen Gilchrist. Not to mention Geoffrey Chaucer.

The Prince of Darkness. Used by Sharon Penman, Paul Doherty, Jean Plaidy, Emma Dorothy Eliza Nevitte Southworth, Susanna Firth, Ray Russell, and Patricia Dexheimer, just to list a few. And Ozzy Osbourne had a go at it too.

The Sun(ne) in Splendo(u)r. Used by Sharon Penman, Jean Plaidy, Juliet Dymoke, Colin Maxwell, and Thomas Burke. There’s also a book called Splendour in the Sun, which got me to humming an immensely annoying 1970’s song called “Seasons in the Sun” (“We had joy, we had fun, we had seasons in the sun”). Quick, someone play some Ozzy Osbourne.

Gay Lord Robert. Used only by Jean Plaidy as far as I know (in a 1971 novel about Robert Dudley), but it takes a very, very manly man to go into Barnes and Noble nowadays and declare, in ringing tones, “I would like to order Gay Lord Robert.”

Then again, my husband once walked into a bookstore and ordered a book called The Brave Little Toaster for me. A manly man, indeed.

Sunday, July 09, 2006

My New Advertising Campaign, and Chanel Pearls of Wisdom

Just when I was beginning to wonder how I would next promote my novel, Alianor, through Bourgeois Nerd, pointed toward The Advertising Slogan Generator. Here are just a few. I'm on my way to have the T-shirts printed now:

I Can't Believe It's Not Traitor's Wife

You've Always Got Time for Traitor's Wife

A Traitor's Wife a Day Helps You Work, Rest and Play

My Goodness, My Traitor's Wife!

Give the Dog a Traitor's Wife

It may be, however, that I don't need a campaign, because excerpts from my back cover copy are showing up in decidedly weird places. What Eleanor de Clare and fourteenth-century England have to do with "Your Health and Air Cleaners" is a deep mystery to me, and how my jacket copy ended up on "Chanel Pearl Sunglasses" is an equal mystery, but at least the Chanel pearl sunglasses sound pretty classy. I'll look for some the next time I'm shopping, if I haven't spent all of my money on health and air cleaners.

I Can't Believe It's Not Traitor's Wife

You've Always Got Time for Traitor's Wife

A Traitor's Wife a Day Helps You Work, Rest and Play

My Goodness, My Traitor's Wife!

Give the Dog a Traitor's Wife

It may be, however, that I don't need a campaign, because excerpts from my back cover copy are showing up in decidedly weird places. What Eleanor de Clare and fourteenth-century England have to do with "Your Health and Air Cleaners" is a deep mystery to me, and how my jacket copy ended up on "Chanel Pearl Sunglasses" is an equal mystery, but at least the Chanel pearl sunglasses sound pretty classy. I'll look for some the next time I'm shopping, if I haven't spent all of my money on health and air cleaners.

Friday, July 07, 2006

Maybe Katharine Hepburn Would Have Helped?

Being in that King John kind of mood, I've been reading Myself as Witness, a 1979 historical novel by James Goldman, best known as the author of the play The Lion in Winter. When you've written a play full of zingers like "Of course he has a knife, he always has a knife, we all have knives! It's 1183 and we're barbarians!" it's sort of hard to repeat one's success, so that should be borne in mind here.

I left this novel with mixed feelings. It's told by Giraldus Cambrensis, an aged man who's hauled out of his retirement in Lincoln to serve as John's chronicler, and it covers the last four years of John's reign. Goldman notes that in his earlier works, he followed convention and treated John as violent, unstable, and unprincipled; here, he says, he took a more balanced view.

Unfortunately, were it not for the author's note, I would have had a hard time deciding exactly what view Goldman took of John. This, I think, is the main problem with this book--that the character of John remains curiously unfocused, opaque. We see John's temper, his flashes of insight, his bitter wit, his intelligence, but it's never quite clear what motivates his actions or how he sees himself. I would say that this is because of the limitations of the form here, a first-person narrative by Giraldus told in diary style, except for the fact that other characters are very sharply etched for us. Isabelle of Angouleme, for instance, is depicted vividly not as the usual sex kitten but as an intelligent, frustrated woman. Giraldus himself, though mostly cast in the role of observer and occasional confidant, is a memorable character. William Marshal is done well here, in the thankless role as a voice of reason ("I've had enough of you Plantagenets," he says toward the end.)

Aside from my frustration over the somewhat hazy picture of John (and who knows, maybe this is what the reader is supposed to feel, that one can never really truly know another person), this book has many merits, and it's certainly worth reading. It's very well written, with some vivid scenes and sharp turns of phrase, and the last few pages, covering John's last days, are particularly well done--it's the part of the novel, in fact, where I at last began to feel I was getting a clear sense of John's character. And given that John so often comes across in historical novels as a stage villain, doing everything but twirling a moustache and crying "Aha!" every two pages, I give Goldman high marks for avoiding caricature. I just wish he had delved a little deeper here.

As I speak, Innocent Traitor by Alison Weir is making its way over the Atlantic toward me, so soon I'll be doing a rare blog for me: a review of a 2006 novel!

I left this novel with mixed feelings. It's told by Giraldus Cambrensis, an aged man who's hauled out of his retirement in Lincoln to serve as John's chronicler, and it covers the last four years of John's reign. Goldman notes that in his earlier works, he followed convention and treated John as violent, unstable, and unprincipled; here, he says, he took a more balanced view.

Unfortunately, were it not for the author's note, I would have had a hard time deciding exactly what view Goldman took of John. This, I think, is the main problem with this book--that the character of John remains curiously unfocused, opaque. We see John's temper, his flashes of insight, his bitter wit, his intelligence, but it's never quite clear what motivates his actions or how he sees himself. I would say that this is because of the limitations of the form here, a first-person narrative by Giraldus told in diary style, except for the fact that other characters are very sharply etched for us. Isabelle of Angouleme, for instance, is depicted vividly not as the usual sex kitten but as an intelligent, frustrated woman. Giraldus himself, though mostly cast in the role of observer and occasional confidant, is a memorable character. William Marshal is done well here, in the thankless role as a voice of reason ("I've had enough of you Plantagenets," he says toward the end.)

Aside from my frustration over the somewhat hazy picture of John (and who knows, maybe this is what the reader is supposed to feel, that one can never really truly know another person), this book has many merits, and it's certainly worth reading. It's very well written, with some vivid scenes and sharp turns of phrase, and the last few pages, covering John's last days, are particularly well done--it's the part of the novel, in fact, where I at last began to feel I was getting a clear sense of John's character. And given that John so often comes across in historical novels as a stage villain, doing everything but twirling a moustache and crying "Aha!" every two pages, I give Goldman high marks for avoiding caricature. I just wish he had delved a little deeper here.

As I speak, Innocent Traitor by Alison Weir is making its way over the Atlantic toward me, so soon I'll be doing a rare blog for me: a review of a 2006 novel!

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

My Favorite Constitutional Amendment

Happy Fourth of July! If you're in the USA and you're reading, ranting, raving, or writing today, take a moment to appreciate the First Amendment to the Constitution:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Saturday, July 01, 2006

A Love Story Set in Wales

I’ve heard good things about John Cowper Powys’ historical novel Owen Glendower, but haven’t had the inclination to wade through it yet. Instead, I bought a copy of White Lion, Red Dragon, a 2003 historical novel by Nobilia Paen about the marriage of Edmund Mortimer to Catherine, daughter of Owen Glendower, here spelled Owain Glyn Dŵr. (An interesting feature of this book is that the back jacket copy is in both English and Welsh.) It’s available on Amazon.uk.

The author describes this as a love story, and it is, without being a romance novel. Catherine, called Cathi, is forced to disguise herself as a boy to evade her father’s enemies. She falls into the hands of a farm couple who put her to work, still in her guise as a lad. When Edmund Mortimer is injured and taken prisoner, she nurses him, and nature takes its course when a recovering Edmund stumbles upon Cathi bathing. The couple gain their freedom and marry, bringing Edmund over to the Glendower cause.

I found Cathi and Edmund to be extremely likeable characters, presented by Paen with affection, sympathy, and even some gentle humor. Cathi remains sweet and somewhat naïve even after tragedy after tragedy strikes, bearing her trials with admirable fortitude. Edmund, though brave, kindly, and good to his dependents, is not always the sharpest tool in the shed: it takes him two full pages to get the hint after an older woman comments knowingly on the cause of Cathi’s sudden nausea.

Having a deep dislike for novels featuring heroines who have mystical visions or who foretell the future (though never as helpfully as one might wish, and never enough to spoil the plot), and having found that such heroines often seem to crop up in historical novels about Wales, I was relieved to find a dearth of visionaries here. And though this is a love story between two attractive young people, we’re spared the endless descriptions of the protagonists’ physical perfection that often figure in such tales.

White Lion, Red Dragon is narrated in the third person but mostly from Cathi’s point of view, so most of the historical events unfold as they are told to Cathi. This can be confusing at times and also somewhat limiting, as major historical figures like Hotspur and Glendower himself appear only briefly here. It would also have been nice for the author in her short note to provide a little more detail as to the likely fate of Edmund and Cathi’s son, Lionel, instead of the unenlightening comment that Adam of Usk “knew a very great deal more than he dared to write.”

This novel isn’t an epic tale in the tradition of Sharon Penman or Nigel Tranter; those who are looking for something like that here will probably be disappointed. As a moving love story between two good people whose happiness is tragically cut short by political upheaval, however, White Lion, Red Dragon is well worth reading.

The author describes this as a love story, and it is, without being a romance novel. Catherine, called Cathi, is forced to disguise herself as a boy to evade her father’s enemies. She falls into the hands of a farm couple who put her to work, still in her guise as a lad. When Edmund Mortimer is injured and taken prisoner, she nurses him, and nature takes its course when a recovering Edmund stumbles upon Cathi bathing. The couple gain their freedom and marry, bringing Edmund over to the Glendower cause.

I found Cathi and Edmund to be extremely likeable characters, presented by Paen with affection, sympathy, and even some gentle humor. Cathi remains sweet and somewhat naïve even after tragedy after tragedy strikes, bearing her trials with admirable fortitude. Edmund, though brave, kindly, and good to his dependents, is not always the sharpest tool in the shed: it takes him two full pages to get the hint after an older woman comments knowingly on the cause of Cathi’s sudden nausea.

Having a deep dislike for novels featuring heroines who have mystical visions or who foretell the future (though never as helpfully as one might wish, and never enough to spoil the plot), and having found that such heroines often seem to crop up in historical novels about Wales, I was relieved to find a dearth of visionaries here. And though this is a love story between two attractive young people, we’re spared the endless descriptions of the protagonists’ physical perfection that often figure in such tales.

White Lion, Red Dragon is narrated in the third person but mostly from Cathi’s point of view, so most of the historical events unfold as they are told to Cathi. This can be confusing at times and also somewhat limiting, as major historical figures like Hotspur and Glendower himself appear only briefly here. It would also have been nice for the author in her short note to provide a little more detail as to the likely fate of Edmund and Cathi’s son, Lionel, instead of the unenlightening comment that Adam of Usk “knew a very great deal more than he dared to write.”

This novel isn’t an epic tale in the tradition of Sharon Penman or Nigel Tranter; those who are looking for something like that here will probably be disappointed. As a moving love story between two good people whose happiness is tragically cut short by political upheaval, however, White Lion, Red Dragon is well worth reading.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)