As promised, here are my ten favorite historical fiction novels that I read in 2006. Some were published this year, others were published years ago. Here they are, in no particular order:

The Boleyn Inheritance by Philippa Gregory (Jane Rochford, Anne of Cleves, Katherine Howard)

Mary by Janis Cooke Newman (Mary Todd Lincoln)

Abundance by Sena Jeter Naslund (Marie Antoinette)

Innocent Traitor by Alison Weir (Lady Jane Grey)

Mary, Queen of Scotland and the Isles by Margaret George (Mary, Queen of Scots)

Fatal Majesty by Reay Tannahill (Mary, Queen of Scots)

The Seventh Son by Reay Tannahill (Richard III)

The Ivy Crown by Mary Luke (Katherine Parr)

The Severed Crown by Jane Lane (Charles I)

The Young and Lonely King by Jane Lane (Charles I)

Other favorites: A Lady Raised High by Laurien Gardner (Anne Boleyn), The Last Queen by C. W. Gortner (Juana the Mad), The Lord of Misrule by Eve Trevaskis (Edward II and Piers Gaveston), The Pleasures of Love by Jean Plaidy (Catherine of Braganza, reviewed on my Jean Plaidy blog), Loving Will Shakespeare by Carolyn Meyer (Anne Hathaway), Gatsby's Girl by Caroline Preston (F. Scott Fitzgerald's girlfriend Ginevra King), The Sceptre and the Rose by Doris Leslie (Catherine of Braganza), and My Lady of Cleves by Margaret Campbell Barnes (Anne of Cleves). I could add some more, but it's getting late.

Aside from reflecting my weakness for books about British royalty, what do these books have in common? Overwhelmingly, it's their depiction of character; all feature likable, yet flawed heroes and heroines. Add to that vivid, realistic dialogue and a distinct narrative voice in most cases, and I was hooked.

I may not be blogging again until after the New Year, so Happy New Year!

Medieval History, and Tudors Too!

Thursday, December 28, 2006

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

Catnip for Christmas

I promise this will be my last cute animal picture for 2006. After that, we'll move back to historical fiction. But after my daughter took this video of Baxter opening a container of catnip on Christmas day, I couldn't resist posting it:

Anyway, since many bloggers have been posting their Top 10 books for 2006, I will be following suit before the end of the year. (I'm still pondering the matter.)

On the nonfiction front, I got Eamon Duffy's Marking the Hours: English People and Their Prayers 1240-1570 for a Christmas present. For those interested in medieval history and/or religious history, I recommend it highly. Fascinating text, beautiful four-color illustrations throughout.

Anyway, since many bloggers have been posting their Top 10 books for 2006, I will be following suit before the end of the year. (I'm still pondering the matter.)

On the nonfiction front, I got Eamon Duffy's Marking the Hours: English People and Their Prayers 1240-1570 for a Christmas present. For those interested in medieval history and/or religious history, I recommend it highly. Fascinating text, beautiful four-color illustrations throughout.

Monday, December 25, 2006

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Onslow the Sweater Guy

First, a housekeeping note: I just updated my template tonight. In the process, some of my newer links disappeared. I believe I restored them all, but if I've left yours out (or if you'd like me to add a link now), just let me know.

Our dog Boswell has a brother named Merritt, who is quite a bit smaller. Merritt, who lives with my parents, was kind enough to lend Boswell his red sweater for Christmas pictures, but it turned out to be way too small for him. It did, however, fit Onslow purr-fectly. (You know I couldn't resist that.)

Speaking of pictures, a high school student in Rhode Island posed for his senior yearbook photo wearing chain mail and carrying a sword. (He's a member of the Society for Creative Anachronism.) The principal, however, claimed that the sword violated the school's "zero tolerance" weapons policy, despite the fact that the school's own mascot, a patriot, totes a weapon. The matter is now in court.

Personally, I say let the kid have his sword. Trust me, it's a lot less scary than the pastel, checked, or plaid polyester suits the senior boys are wearing in my high school yearbook.

Our dog Boswell has a brother named Merritt, who is quite a bit smaller. Merritt, who lives with my parents, was kind enough to lend Boswell his red sweater for Christmas pictures, but it turned out to be way too small for him. It did, however, fit Onslow purr-fectly. (You know I couldn't resist that.)

Speaking of pictures, a high school student in Rhode Island posed for his senior yearbook photo wearing chain mail and carrying a sword. (He's a member of the Society for Creative Anachronism.) The principal, however, claimed that the sword violated the school's "zero tolerance" weapons policy, despite the fact that the school's own mascot, a patriot, totes a weapon. The matter is now in court.

Personally, I say let the kid have his sword. Trust me, it's a lot less scary than the pastel, checked, or plaid polyester suits the senior boys are wearing in my high school yearbook.

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

This Blog's Stop on the Advent Tour

We'll start this visit on Marg's and Kaliana's Advent Blog Tour with a very special guest:

In the mood for a movie this Christmas? Let me recommend Kenneth Branagh's In the Bleak Midwinter (also known as A Midwinter's Tale), about a group of actors putting on a Christmastime production of Hamlet. It's a funny, sweet story. (It is rated "R," but the rating seems way overcautious to me--there's no violence or sex, and the language isn't saltier than some of what gets on television these days.)

Read "A Christmas Carol" for the umpteenth time? Try "The Haunted Man," one of Charles Dickens's lesser known Christmas stories, this year instead.

And for our feature presentation, "Christmas 1484 With Richard III," see the post below.

In the mood for a movie this Christmas? Let me recommend Kenneth Branagh's In the Bleak Midwinter (also known as A Midwinter's Tale), about a group of actors putting on a Christmastime production of Hamlet. It's a funny, sweet story. (It is rated "R," but the rating seems way overcautious to me--there's no violence or sex, and the language isn't saltier than some of what gets on television these days.)

Read "A Christmas Carol" for the umpteenth time? Try "The Haunted Man," one of Charles Dickens's lesser known Christmas stories, this year instead.

And for our feature presentation, "Christmas 1484 With Richard III," see the post below.

Christmas 1484 with Richard III: A Playlet

Scene 1: Westminster Hall is bedecked with greenery and tapestries covered with little white boars as King Richard III and Queen Anne enter. They look around admiringly.

Anne: Isn’t it beautiful? (Coughs) I beg your pardon. And look, I’ve left a couple of places vacant just in case your nephews Edward and Richard return for Christmas from their grand tour of the Continent.

Richard: How thoughtful, my dear. (Aside) What am I going to tell her next? I can't keep them on the damn Grand Tour forever.

Scene 2: Some time later. The king and queen are mingling with their guests.

Anne: Here comes your brother’s daughter Elizabeth. I do think she's bearing up pretty well after being in sanctuary all that time, don't you? And look, Richard! Just in case the poor girl was feeling sad this Christmas I had her dress made from the same material as mine. Isn’t it beautiful?

Richard: (Eyes popping) Yes. She—er—it is.

(Elizabeth, heading toward the royal couple, passes courtiers)

Courtiers: Wowsa!

Elizabeth: (Aside) And I thought it was going to be no fun being a bastard. (Curtsies to Richard) I wish you good tidings of the season, your grace. Oh, and your grace too. (Turns to Anne) How are you feeling, your grace?

Anne: Perfectly well, thank you. (Coughs for five minutes or so) Excuse me for a few minutes.

Elizabeth: (Taking out a slip of paper from a pouch she wears at her side) I thought she’d never stop coughing. Do you know when the doctors say she’ll die? This is what I want engraved on our plate once we’re married, Dickon.

Richard: Sweetheart, I told you to keep calling me “uncle” in public.

Elizabeth: (Pouting) All right, Uncle. But what do you think about the engraving?

Richard: Beautiful. Er— Anne?

Anne: What are you showing your uncle, dear?

Elizabeth: Oh, that would spoil your surprise, your grace. (Scampers off)

Anne: What a sweet girl. We really need to find a husband for her, dear.

Richard: Oh, I’m working on it.

Anne: You think of everything.

Richard: Welcome, Lord Stanley! How goes it with your wife?

Stanley: My wife?

Richard: Yes, your wife, Margaret Beaufort. The woman you have under house arrest on my orders.

Stanley: Oh, yes, my wife. She is very well.

Richard: She doesn’t find her confinement disagreeable?

Stanley: Oh, she finds ways to pass the time.

Richard: And how is that son of hers? John, no, Edward, no, Henry. That’s it. Henry Tudor.

Stanley: Him. I have no idea. I don’t hear from him. She never hears from him. We never hear from him. Frankly, I think sometimes my wife forgets he’s even alive, he’s been abroad so long.

Richard: Indeed. Well, a merry Christmas to you, Lord Stanley. (Aside) Lying bastard.

Stanley: And a merry Christmas to you, your grace. (Aside) Not “your grace” for long if Maggie has her way. (Exits)

Richard: Oh, hello, Mother.

Cecily: Hello, dear.

Richard: Are you enjoying your Christmas?

Cecily: As much as I can since you spread that nasty rumor that I had been unfaithful to your father and that your brothers weren't his children.

Richard: Not that again. It was nothing personal, Mum. We went through this last Christmas.

Cecily: Yes, and we’ll go through it this Christmas too, and the Christmas after that, and the Christmas after that. And you know why? Because I’m your mother and I can say to you whatever I please. Even if you are the king. And don't get me started on how you got to be the king. Your dear little nephews—

Richard: Mother, how about going on pilgrimage next Christmas? I’ll pay for everything.

Scene 3: The royal bedchamber. Richard is lying alone in the royal bed. Suddenly a spirit appears, shrouded in a deep black garment that conceals all of it except for one outstretched hand. Richard stirs and wakes.

Richard: What—? (Aside) I knew that last cup of wine was a big mistake.

Spirit: I am the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come.

Richard: The what?

Spirit: You’d understand better if you were living about 400 years later. By then, a chap named Charles Dickens— But I’ve got other visits to pay tonight. Let’s discuss Christmas Yet to Come.

Richard: Tell me, O Spirit.

Spirit: Well, to begin with, your wife is going to die. I know you’ve been expecting that, but it’s not going to work out as you planned. You’re going to have to give up your plans to marry that nubile little niece of yours.

Richard: No nubile niece!

Spirit: It goes downhill from there. She’s going to marry Henry Tudor.

Richard: Not Tudor, no! Not Tudor!

Spirit: They’re going to have sons, and one of the sons is going to have six wives.

Richard: Six wives! I can’t even marry two! Or can I? Do I get to marry anyone else? Do I get to have living children?

Spirit: Sorry, no. Now, how can I put this? Well, in your case there’s not going to be a Christmas Yet to Come. This is your last one. Hope the food was good tonight.

Richard: Spirit?

Spirit: You’re going to die in battle before the end of the coming year, and Tudor is going to take the crown. Then he gets your niece, and the son with the six wives becomes king after him. You’ll be the end of the Plantagenet dynasty.

Richard: (After a long silence) I killed the little brats for this?

Spirit: I'm afraid so. But you will fight pretty well in that last battle, aside from getting killed. That's something.

Richard: Spirit, what I can do to change this dire future?

Spirit: Not a blessed thing. Too many people are going to be making a living writing books about you and the king with the six wives. But there is an upside to all of this.

Richard: Tell me, O Spirit.

Spirit: Your reputation will be bad, and a glover’s son named William Shakespeare will make it even worse. You’ll even be depicted with a hump on your back. But after 500 years or so, it will start to get better. There will be a society devoted entirely to improving your reputation. There will be publications devoted to you. Your enemies will be slandered. You’ll be hard-pressed to find a novel about you where you aren’t the good guy. Women in particular will love you. Everyone will blame someone else for the Princes in the Tower, and people won’t even care that you executed Hastings, Rivers, Grey, Vaughan, and Haute on trumped-up charges. You’ll be everybody’s favorite dead king.

Richard: So. Tudor gets the girl and the crown, and I get the Richard III Society and the adoring women?

Spirit: Yes.

Richard: (Sighing) Well, there are tradeoffs in life, aren’t there? Merry Christmas, Spirit.

Spirit: Merry Christmas. And to all a good night.

Anne: Isn’t it beautiful? (Coughs) I beg your pardon. And look, I’ve left a couple of places vacant just in case your nephews Edward and Richard return for Christmas from their grand tour of the Continent.

Richard: How thoughtful, my dear. (Aside) What am I going to tell her next? I can't keep them on the damn Grand Tour forever.

Scene 2: Some time later. The king and queen are mingling with their guests.

Anne: Here comes your brother’s daughter Elizabeth. I do think she's bearing up pretty well after being in sanctuary all that time, don't you? And look, Richard! Just in case the poor girl was feeling sad this Christmas I had her dress made from the same material as mine. Isn’t it beautiful?

Richard: (Eyes popping) Yes. She—er—it is.

(Elizabeth, heading toward the royal couple, passes courtiers)

Courtiers: Wowsa!

Elizabeth: (Aside) And I thought it was going to be no fun being a bastard. (Curtsies to Richard) I wish you good tidings of the season, your grace. Oh, and your grace too. (Turns to Anne) How are you feeling, your grace?

Anne: Perfectly well, thank you. (Coughs for five minutes or so) Excuse me for a few minutes.

Elizabeth: (Taking out a slip of paper from a pouch she wears at her side) I thought she’d never stop coughing. Do you know when the doctors say she’ll die? This is what I want engraved on our plate once we’re married, Dickon.

Richard: Sweetheart, I told you to keep calling me “uncle” in public.

Elizabeth: (Pouting) All right, Uncle. But what do you think about the engraving?

Richard: Beautiful. Er— Anne?

Anne: What are you showing your uncle, dear?

Elizabeth: Oh, that would spoil your surprise, your grace. (Scampers off)

Anne: What a sweet girl. We really need to find a husband for her, dear.

Richard: Oh, I’m working on it.

Anne: You think of everything.

Richard: Welcome, Lord Stanley! How goes it with your wife?

Stanley: My wife?

Richard: Yes, your wife, Margaret Beaufort. The woman you have under house arrest on my orders.

Stanley: Oh, yes, my wife. She is very well.

Richard: She doesn’t find her confinement disagreeable?

Stanley: Oh, she finds ways to pass the time.

Richard: And how is that son of hers? John, no, Edward, no, Henry. That’s it. Henry Tudor.

Stanley: Him. I have no idea. I don’t hear from him. She never hears from him. We never hear from him. Frankly, I think sometimes my wife forgets he’s even alive, he’s been abroad so long.

Richard: Indeed. Well, a merry Christmas to you, Lord Stanley. (Aside) Lying bastard.

Stanley: And a merry Christmas to you, your grace. (Aside) Not “your grace” for long if Maggie has her way. (Exits)

Richard: Oh, hello, Mother.

Cecily: Hello, dear.

Richard: Are you enjoying your Christmas?

Cecily: As much as I can since you spread that nasty rumor that I had been unfaithful to your father and that your brothers weren't his children.

Richard: Not that again. It was nothing personal, Mum. We went through this last Christmas.

Cecily: Yes, and we’ll go through it this Christmas too, and the Christmas after that, and the Christmas after that. And you know why? Because I’m your mother and I can say to you whatever I please. Even if you are the king. And don't get me started on how you got to be the king. Your dear little nephews—

Richard: Mother, how about going on pilgrimage next Christmas? I’ll pay for everything.

Scene 3: The royal bedchamber. Richard is lying alone in the royal bed. Suddenly a spirit appears, shrouded in a deep black garment that conceals all of it except for one outstretched hand. Richard stirs and wakes.

Richard: What—? (Aside) I knew that last cup of wine was a big mistake.

Spirit: I am the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come.

Richard: The what?

Spirit: You’d understand better if you were living about 400 years later. By then, a chap named Charles Dickens— But I’ve got other visits to pay tonight. Let’s discuss Christmas Yet to Come.

Richard: Tell me, O Spirit.

Spirit: Well, to begin with, your wife is going to die. I know you’ve been expecting that, but it’s not going to work out as you planned. You’re going to have to give up your plans to marry that nubile little niece of yours.

Richard: No nubile niece!

Spirit: It goes downhill from there. She’s going to marry Henry Tudor.

Richard: Not Tudor, no! Not Tudor!

Spirit: They’re going to have sons, and one of the sons is going to have six wives.

Richard: Six wives! I can’t even marry two! Or can I? Do I get to marry anyone else? Do I get to have living children?

Spirit: Sorry, no. Now, how can I put this? Well, in your case there’s not going to be a Christmas Yet to Come. This is your last one. Hope the food was good tonight.

Richard: Spirit?

Spirit: You’re going to die in battle before the end of the coming year, and Tudor is going to take the crown. Then he gets your niece, and the son with the six wives becomes king after him. You’ll be the end of the Plantagenet dynasty.

Richard: (After a long silence) I killed the little brats for this?

Spirit: I'm afraid so. But you will fight pretty well in that last battle, aside from getting killed. That's something.

Richard: Spirit, what I can do to change this dire future?

Spirit: Not a blessed thing. Too many people are going to be making a living writing books about you and the king with the six wives. But there is an upside to all of this.

Richard: Tell me, O Spirit.

Spirit: Your reputation will be bad, and a glover’s son named William Shakespeare will make it even worse. You’ll even be depicted with a hump on your back. But after 500 years or so, it will start to get better. There will be a society devoted entirely to improving your reputation. There will be publications devoted to you. Your enemies will be slandered. You’ll be hard-pressed to find a novel about you where you aren’t the good guy. Women in particular will love you. Everyone will blame someone else for the Princes in the Tower, and people won’t even care that you executed Hastings, Rivers, Grey, Vaughan, and Haute on trumped-up charges. You’ll be everybody’s favorite dead king.

Richard: So. Tudor gets the girl and the crown, and I get the Richard III Society and the adoring women?

Spirit: Yes.

Richard: (Sighing) Well, there are tradeoffs in life, aren’t there? Merry Christmas, Spirit.

Spirit: Merry Christmas. And to all a good night.

Monday, December 18, 2006

McMansions and More

Not far from our house, a development of McMansions has begun construction, and some homes are finally available for walk-through. Being curious to see how the other half lives, my family and I went out over the weekend and walked around a couple.

No doubt about it, these houses do have lots of space. If you were mad at your relatives, you could pretty much avoid them for days at a time. In fact, your cars wouldn't even have to talk to each other, because several of these places had two garages--just in case, I suppose, your Hummer gave your Mercedes-Benz bad vibes.

Unfortunately, there was one glaring design flaw. When I entered the first house, I was transfixed by the built-in bookshelves surrounding the fireplace and indulged in some fairly serious Bookcase Lust. As I was preparing to leave the house, however, I took a last lingering look at the shelves and realized what I hadn't seen before: you couldn't fit hardbacks on these shelves. Not even trade paperbacks. The only thing that would fit on them was small knickknacks and mass-market paperbacks.

Well, that was a deal-killer for me. Where would I put my Dickens? Where would I put my Plaidys? Where would I put my hard-to-find Robert Hale titles? And where would I put The Traitor's Wife? What's the point of spending $750,000 on a house if you can't stretch out on the couch and stare admiringly at one's own book on one's own built-in bookshelves? Does that mean I'd have to take up reading Danielle Steele?

So, no McMansion for me, thank you very much, until I see one that caters to the wishes of the discerning reader. (And, of course, until I address the small matter of affording one.)

Anyway, yesterday I finished reading Jane Lane's Bridge of Sighs (which wouldn't fit on the McMansion's bookshelves either). It's about Mary Beatrice, second wife of James II. I was rather disappointed in it, especially when compared to the other Jane Lane novels I've read, the best of which have a dry wit and a deep sympathy for the main characters. There are a few good moments here, but I never felt that I knew Mary Beatrice or believed in the emotions that we were told she was feeling. I kept reading it because I knew little about the history of the time and was curious to find out what happened, but otherwise I doubt it would have held my interest.

Finally, I've signed up to do a posting for Marg and Kailana’s 2006 Advent Blog Tour. There's been a lot of nice posts so far, and I'm looking forward to reading what comes next. Mine is scheduled for December 21, and will feature Christmas of 1484 with Richard III. (If you're a diehard Ricardian without a sense of humor--not that you probably read this blog if you are--pass this one by.)

No doubt about it, these houses do have lots of space. If you were mad at your relatives, you could pretty much avoid them for days at a time. In fact, your cars wouldn't even have to talk to each other, because several of these places had two garages--just in case, I suppose, your Hummer gave your Mercedes-Benz bad vibes.

Unfortunately, there was one glaring design flaw. When I entered the first house, I was transfixed by the built-in bookshelves surrounding the fireplace and indulged in some fairly serious Bookcase Lust. As I was preparing to leave the house, however, I took a last lingering look at the shelves and realized what I hadn't seen before: you couldn't fit hardbacks on these shelves. Not even trade paperbacks. The only thing that would fit on them was small knickknacks and mass-market paperbacks.

Well, that was a deal-killer for me. Where would I put my Dickens? Where would I put my Plaidys? Where would I put my hard-to-find Robert Hale titles? And where would I put The Traitor's Wife? What's the point of spending $750,000 on a house if you can't stretch out on the couch and stare admiringly at one's own book on one's own built-in bookshelves? Does that mean I'd have to take up reading Danielle Steele?

So, no McMansion for me, thank you very much, until I see one that caters to the wishes of the discerning reader. (And, of course, until I address the small matter of affording one.)

Anyway, yesterday I finished reading Jane Lane's Bridge of Sighs (which wouldn't fit on the McMansion's bookshelves either). It's about Mary Beatrice, second wife of James II. I was rather disappointed in it, especially when compared to the other Jane Lane novels I've read, the best of which have a dry wit and a deep sympathy for the main characters. There are a few good moments here, but I never felt that I knew Mary Beatrice or believed in the emotions that we were told she was feeling. I kept reading it because I knew little about the history of the time and was curious to find out what happened, but otherwise I doubt it would have held my interest.

Finally, I've signed up to do a posting for Marg and Kailana’s 2006 Advent Blog Tour. There's been a lot of nice posts so far, and I'm looking forward to reading what comes next. Mine is scheduled for December 21, and will feature Christmas of 1484 with Richard III. (If you're a diehard Ricardian without a sense of humor--not that you probably read this blog if you are--pass this one by.)

Thursday, December 14, 2006

So Why Don't I Like Fantasy? Beats Me . . .

There was a post on Carla's blog the other day about historical fantasy, and as I mentioned on the comments section there, I've never cared for fantasy. I've been trying to figure out why. It's not that I have a Gradgrindian aversion to fancy; after all, there's a miniature Christmas tree in my kitchen that opens up its mouth (yes, its mouth, cleverly concealed under its branches) and sings "Jingle Bells" when you wave a hand in front of it. It's not that I'm a religious fanatic who sees something sinister in Harry Potter; quite the contrary. But for whatever reason, fantasy, as well as science fiction, has never appealed to me.

In the end, I suppose it's like chocolate ice cream. I don't like it. I know lots of people love it. I know there are excellent varieties of it. I'll buy it for my family. I'll even make an effort to eat it now and again to be polite. I'll never attempt to dissuade someone else from eating and enjoying it. But I just plain don't like it. Give me vanilla any day.

That being said, I'm not immune entirely to fantasy, it turns out, at least not at the level of wanting to see what happens next. I volunteer at my daughter's school library shelving books once a week. I come in at the same time a second-grade class comes in for its library hour, and part of the hour, of course, is story time. So for the past few weeks, I've been listening, with the second graders, to one of the librarians read a volume in "The Magic Tree House" series. The series, from what I can tell, involves a couple of modern-day kids who go to, well, a magic tree house, and get transported back into the past. Once the kids reach the past, there's always some crisis that only they can solve.

Anyway, in this volume--I haven't caught the name--the kids have been taken back to Camelot, only to find that the denizens of the Round Table are having a perfectly miserable Christmas, evidently because the leading knights have gone missing and none of the people left have the courage to go looking for them. Our modern-day kids, being a plucky pair, immediately volunteer, and just yesterday, they located the missing knights, who have all been put under some sort of a spell that makes them dance endlessly until they dance themselves to death. When the bell rang yesterday, the kids had hit on a solution: join the dancing circle, keep from falling under the spell themselves, and pull the dancers out of the circle, thereby breaking the spell and return everyone to Camelot. Things were looking dire, though, because it appeared that the kids might not be able to resist the spell themselves . . .

I hope this is all wrapped up next week, because I really don't think I can wait until after Christmas break to find out how this all ends up.

In the end, I suppose it's like chocolate ice cream. I don't like it. I know lots of people love it. I know there are excellent varieties of it. I'll buy it for my family. I'll even make an effort to eat it now and again to be polite. I'll never attempt to dissuade someone else from eating and enjoying it. But I just plain don't like it. Give me vanilla any day.

That being said, I'm not immune entirely to fantasy, it turns out, at least not at the level of wanting to see what happens next. I volunteer at my daughter's school library shelving books once a week. I come in at the same time a second-grade class comes in for its library hour, and part of the hour, of course, is story time. So for the past few weeks, I've been listening, with the second graders, to one of the librarians read a volume in "The Magic Tree House" series. The series, from what I can tell, involves a couple of modern-day kids who go to, well, a magic tree house, and get transported back into the past. Once the kids reach the past, there's always some crisis that only they can solve.

Anyway, in this volume--I haven't caught the name--the kids have been taken back to Camelot, only to find that the denizens of the Round Table are having a perfectly miserable Christmas, evidently because the leading knights have gone missing and none of the people left have the courage to go looking for them. Our modern-day kids, being a plucky pair, immediately volunteer, and just yesterday, they located the missing knights, who have all been put under some sort of a spell that makes them dance endlessly until they dance themselves to death. When the bell rang yesterday, the kids had hit on a solution: join the dancing circle, keep from falling under the spell themselves, and pull the dancers out of the circle, thereby breaking the spell and return everyone to Camelot. Things were looking dire, though, because it appeared that the kids might not be able to resist the spell themselves . . .

I hope this is all wrapped up next week, because I really don't think I can wait until after Christmas break to find out how this all ends up.

Thursday, December 07, 2006

Philippa Gregory's Latest

I haven't read much of Philippa Gregory, and up to now, the only novel of hers that I found agreeable was The Constant Princess (and even that, I thought, was repetitive and on the politically correct side). I loathed all of the characters in The Virgin's Lover, so much that I never got past the first few chapters, and though The Other Boleyn Girl had some memorable scenes and vivid characters, the whole thing struck me as smarmy. But I'm always up for another round with Henry VIII and his wives, so I put myself on the library waiting list for The Boleyn Inheritance.

And I'm pleased to report that I enjoyed it immensely.

The Boleyn Inheritance is told by Jane, Lady Rochford, widow of the executed George Boleyn; Anne of Cleves; and Katherine "Kitty" Howard. Jane, self-justifying and self-deceiving, is obsessed with her past yet determined to do whatever she has to do in order to restore her life to its former glamour. Anne, no stupid Flanders mare but a sensible, honorable young woman who longs for freedom and respect, finds that she has exchanged the petty humiliations of her brother's court for the reign of terror of Henry's. Kitty is an airheaded teenager, with an endless capacity to push aside unpleasant realities in favor of her more satisfying preoccupations: young men, jewels, and pretty clothes. Manipulating Jane and Kitty is the sinister Duke of Norfolk, and stalking through all three women's lives is the unpredictable, increasingly tyrannical Henry VIII.

Gregory juggles the heroines' stories masterfully. Even when Anne of Cleves is relegated to the background and the machinations of the Duke of Norfolk and Jane take center stage, Anne remains to comment on what she sees around her. She, the outsider, becomes both the moral center of the novel and the narrator on which the reader can most rely for an accurate perception of events. Kitty's adolescent preoccupations and mercurial character are captured wonderfully, while Jane, morally repulsive as she is, has a normalcy about her that keeps us reading her story and wondering at her motivations.

There's a certain humor here, often quite dark, that was missing altogether in the very earnest Constant Princess. Much of this comes from Kitty's youthful blatherings ("France would be wonderful, except I cannot speak French, or at any rate only "voila!" but surely they must mostly all speak English? And if not, then they can learn?"), but the more cynical Jane Rochford contributes some memorable lines: "If she declares herself Dereham's wife, then she has not then cuckolded the king but only Dereham; and since his head is on London Bridge, he is in no position to complain."

And neither am I. Read this one.

And I'm pleased to report that I enjoyed it immensely.

The Boleyn Inheritance is told by Jane, Lady Rochford, widow of the executed George Boleyn; Anne of Cleves; and Katherine "Kitty" Howard. Jane, self-justifying and self-deceiving, is obsessed with her past yet determined to do whatever she has to do in order to restore her life to its former glamour. Anne, no stupid Flanders mare but a sensible, honorable young woman who longs for freedom and respect, finds that she has exchanged the petty humiliations of her brother's court for the reign of terror of Henry's. Kitty is an airheaded teenager, with an endless capacity to push aside unpleasant realities in favor of her more satisfying preoccupations: young men, jewels, and pretty clothes. Manipulating Jane and Kitty is the sinister Duke of Norfolk, and stalking through all three women's lives is the unpredictable, increasingly tyrannical Henry VIII.

Gregory juggles the heroines' stories masterfully. Even when Anne of Cleves is relegated to the background and the machinations of the Duke of Norfolk and Jane take center stage, Anne remains to comment on what she sees around her. She, the outsider, becomes both the moral center of the novel and the narrator on which the reader can most rely for an accurate perception of events. Kitty's adolescent preoccupations and mercurial character are captured wonderfully, while Jane, morally repulsive as she is, has a normalcy about her that keeps us reading her story and wondering at her motivations.

There's a certain humor here, often quite dark, that was missing altogether in the very earnest Constant Princess. Much of this comes from Kitty's youthful blatherings ("France would be wonderful, except I cannot speak French, or at any rate only "voila!" but surely they must mostly all speak English? And if not, then they can learn?"), but the more cynical Jane Rochford contributes some memorable lines: "If she declares herself Dereham's wife, then she has not then cuckolded the king but only Dereham; and since his head is on London Bridge, he is in no position to complain."

And neither am I. Read this one.

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

To Bibliography or Not to Bibliography?

Here's an excerpt from an interesting article by Julie Bosman, "Loved His New Novel, and What a Bibliography," in today's New York Times about the practice of including bibligraphies in novels:

I'm with Mr. Vollmann. Personally, I regard a bibliography in a historical novel not as a bid for praise or as proof of labor and expertise, but simply as a tool for the reader who might be interested in reading more about the subject. I don't hold the absence of one against an author (there's none in my own book, although I do include an author's note in the book and a list of further reading on my website), but I do appreciate its inclusion. I certainly don't see its being there as pretentious or as a form of bragging. It's an aid to the reader, which the reader can either make use of or ignore.

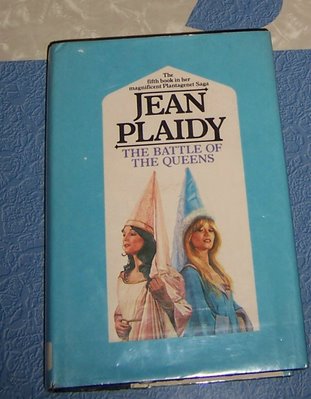

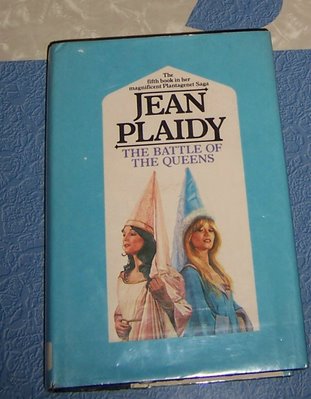

Maybe Mr. Wood just doesn't read much commercial historical fiction, because bibliographies seem to have been quite common in it for some time. Jean Plaidy often included them in her novels (The Battle of the Queens, the one closest to hand on my bookshelf, lists 21 titles that Plaidy consulted), and King's Minions, a 1974 Brenda Honeyman novel about Edward II that I finally acquired yesterday after months of forlorn Googling, has a "Works Consulted" page. Even these now-dated bibliographies can be useful in leading readers to long-out-of-print books that may contain relevant information.

So I say, ignore Mr. Wood. Bring on the bibs (and keep the author's notes coming too, please).

“It’s terribly off-putting,” said James Wood, the literary critic for The New Republic. “It would be very odd if Thomas Hardy had put at the end of all his books, ‘I’m thankful to the Dorset County Chronicle for dialect books from the 18th century.’ We expect authors to do that work, and I don’t see why we should praise them for that work. And I don’t see why they should praise themselves for it.”

Traditionally confined to works of nonfiction, the bibliography has lately been creeping into novels, rankling critics who call it a pretentious extension of the acknowledgments page, which began appearing more than a decade ago and was roundly derided as the tacky literary equivalent of the Oscar speech. Purists contend that novelists have always done research, particularly in books like “Madame Bovary” that were inspired by real-life events, yet never felt a bibliography was necessary.

And many present-day writers like Thomas Pynchon, most recently in “Against the Day,” put extensive historical research into their novels without citing sources or explaining methods.

But some novelists defend the bibliography, pointing out that for writers who spend months or years doing research for historical novels, a list of sources is proof of labor and expertise. . . .

Of course some fiction writers have always tacked on bibliographies, as William T. Vollmann has done since his first book, “You Bright and Risen Angels,” published in 1987. Mr. Vollmann initially did it because the book was first published in Britain, and he wasn’t sure how many sources he was expected to cite according to British laws, he said.

But now, Mr. Vollmann says, he does it as a service to readers. “I think it’s nice for a reader to have the information available,” he said. “Let’s say somebody gets interested in a character, or is disbelieving of something I had a character do. He can look in the back of the book.” . . .

I'm with Mr. Vollmann. Personally, I regard a bibliography in a historical novel not as a bid for praise or as proof of labor and expertise, but simply as a tool for the reader who might be interested in reading more about the subject. I don't hold the absence of one against an author (there's none in my own book, although I do include an author's note in the book and a list of further reading on my website), but I do appreciate its inclusion. I certainly don't see its being there as pretentious or as a form of bragging. It's an aid to the reader, which the reader can either make use of or ignore.

Maybe Mr. Wood just doesn't read much commercial historical fiction, because bibliographies seem to have been quite common in it for some time. Jean Plaidy often included them in her novels (The Battle of the Queens, the one closest to hand on my bookshelf, lists 21 titles that Plaidy consulted), and King's Minions, a 1974 Brenda Honeyman novel about Edward II that I finally acquired yesterday after months of forlorn Googling, has a "Works Consulted" page. Even these now-dated bibliographies can be useful in leading readers to long-out-of-print books that may contain relevant information.

So I say, ignore Mr. Wood. Bring on the bibs (and keep the author's notes coming too, please).

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Two Wives and a Girlfriend

I got my copy of the Historical Novels Review today. It's a great publication for readers and writers of historical fiction, and in case you're new to this blog, I contribute some reviews to it. So without further ado, here are three of my reviews from the November 2006 issue: Mary by Janis Cooke Newman (about Mary Tood Lincoln), Gatsby's Girl by Caroline Preston (F. Scott Fitzgerald's old flame), and Loving Will Shakespeare by Carolyn Meyer (Anne Hathaway). I enjoyed each of them very much.

Mary: A Novel

Janis Cooke Newman

Committed to the Bellevue Place Sanitarium by her eldest son in 1875, Mary Todd Lincoln begins to write the story of her life in order to pass her sleepless nights and to keep herself sane—and also to gain the love of her cold-natured son. As Mary reflects upon her past, she also makes new acquaintances in the present, notably that of Minnie Judd, a fellow sanitarium inmate.

Minnie is starving herself in order to win the love of her indifferent husband, and Mary soon recognizes a kindred spirit in the young woman, for Mary’s life has also been an elusive quest for love, thwarted sometimes by death, sometimes by the frigidity of those whose affections she seeks to gain. Minnie’s quest, however, is doomed to defeat, while Mary’s ultimately ends in self-discovery.

Mary, however, is far more than just an account of a woman’s search for love. The novel is also a story of the Lincoln marriage, a mutually loving one marked in turn by defeat and triumph, by shared happiness and shared tragedy. Both Lincoln and Mary are vividly drawn characters, but Mary, as the center of the novel, is inevitably the more so. Her charm and wit are present throughout this book, but her faults—her temper, her extravagance, even on one occasion her infidelity—are amply on display. The novel is also, of course, one of a nation divided by civil war, and this gives rise to some memorable scenes, particularly a postwar visit to Richmond where the Lincolns get very different receptions from black Southerners and from white Southerners.

Moving and with an almost palpable compassion for its subject, yet clear-eyed and even humorous at times, this is a book I will be re-reading.

Gatsby’s Girl: A Novel

Caroline Preston

In 1915, F. Scott Fitzgerald met a society girl, Ginevra King, with whom he had a brief romance before she lost interest in him. Gatsby’s Girl, with a Ginevra Perry as the heroine, is loosely based on this episode in Fitzgerald’s life; the author, as she explains in a detailed, informative historical note, has purposely altered characters and events.

Dazzled by a handsome aviator-in-training at a party, fickle Ginevra wastes no time in ridding herself of Fitzgerald, a “silly college boy” with a pronounced taste for highballs who “’writes,’ plays dress-up, and is flunking geometry.” Five years later, Ginevra, married and a mother, realizes that her spurned suitor has become famous and that a female character in his new novel bears a distinct resemblance to herself. From that point on, Ginevra’s and Fitzgerald’s lives will occasionally intersect and parallel each other, with sometimes surprising results.

With Fitzgerald and Ginevra’s romance over, I wondered at first whether Ginevra, the narrator, was going to be able to carry the rest of Gatsby’s Girl by herself. I needn’t have worried, however, for Ginevra turns out to be more than simply a shallow debutante. As she faces an unhappy marriage, a mentally ill child, and the consequences of her own recklessness with increasing maturity, sensitivity, and self-awareness, she gains the reader’s respect. Gatsby’s Girl is an engaging and absorbing novel in which the heroine proves wrong her old boyfriend’s declaration, “There are no second acts in American lives.”

Loving Will Shakespeare

Carolyn Meyer

Just before the plague returns to England, seven-year-old Agnes (Anne) Hathaway and her family are invited to a christening by friends: John and Mary Shakespeare, who have just had a son, William. From that point on, Anne’s and Will’s lives will constantly intersect, even when the pair are miles apart.

Despite the title, this appealing novel is not so much the story of Anne and Will’s courtship and marriage as it is of Anne’s coming of age, though the budding playwright is never very far offstage and the love story does assume prominence in the latter part of the book. Growing up as a yeoman farmer’s daughter, Anne, the narrator, is an ordinary girl but by no means a dull one. She must cope with her difficult stepmother and half-sister, the temptations posed by men, the deaths of loved ones, worries over friends who choose to practice Catholicism, and her increasing fear of spinsterhood, and she does so with resourcefulness and good humor. All of this plays out against the vividly rendered backdrop of life in Elizabethan England: the once-in-a-lifetime excitement of a royal progress, the annual May Day and Yuletide feasts, the periodic visitations of plague and sweating sickness, the daily business of running a farm. These elements make this an engrossing story, one that should appeal to adults as well as to the teens for whom it is intended. Ages 12 and up.

Mary: A Novel

Janis Cooke Newman

Committed to the Bellevue Place Sanitarium by her eldest son in 1875, Mary Todd Lincoln begins to write the story of her life in order to pass her sleepless nights and to keep herself sane—and also to gain the love of her cold-natured son. As Mary reflects upon her past, she also makes new acquaintances in the present, notably that of Minnie Judd, a fellow sanitarium inmate.

Minnie is starving herself in order to win the love of her indifferent husband, and Mary soon recognizes a kindred spirit in the young woman, for Mary’s life has also been an elusive quest for love, thwarted sometimes by death, sometimes by the frigidity of those whose affections she seeks to gain. Minnie’s quest, however, is doomed to defeat, while Mary’s ultimately ends in self-discovery.

Mary, however, is far more than just an account of a woman’s search for love. The novel is also a story of the Lincoln marriage, a mutually loving one marked in turn by defeat and triumph, by shared happiness and shared tragedy. Both Lincoln and Mary are vividly drawn characters, but Mary, as the center of the novel, is inevitably the more so. Her charm and wit are present throughout this book, but her faults—her temper, her extravagance, even on one occasion her infidelity—are amply on display. The novel is also, of course, one of a nation divided by civil war, and this gives rise to some memorable scenes, particularly a postwar visit to Richmond where the Lincolns get very different receptions from black Southerners and from white Southerners.

Moving and with an almost palpable compassion for its subject, yet clear-eyed and even humorous at times, this is a book I will be re-reading.

Gatsby’s Girl: A Novel

Caroline Preston

In 1915, F. Scott Fitzgerald met a society girl, Ginevra King, with whom he had a brief romance before she lost interest in him. Gatsby’s Girl, with a Ginevra Perry as the heroine, is loosely based on this episode in Fitzgerald’s life; the author, as she explains in a detailed, informative historical note, has purposely altered characters and events.

Dazzled by a handsome aviator-in-training at a party, fickle Ginevra wastes no time in ridding herself of Fitzgerald, a “silly college boy” with a pronounced taste for highballs who “’writes,’ plays dress-up, and is flunking geometry.” Five years later, Ginevra, married and a mother, realizes that her spurned suitor has become famous and that a female character in his new novel bears a distinct resemblance to herself. From that point on, Ginevra’s and Fitzgerald’s lives will occasionally intersect and parallel each other, with sometimes surprising results.

With Fitzgerald and Ginevra’s romance over, I wondered at first whether Ginevra, the narrator, was going to be able to carry the rest of Gatsby’s Girl by herself. I needn’t have worried, however, for Ginevra turns out to be more than simply a shallow debutante. As she faces an unhappy marriage, a mentally ill child, and the consequences of her own recklessness with increasing maturity, sensitivity, and self-awareness, she gains the reader’s respect. Gatsby’s Girl is an engaging and absorbing novel in which the heroine proves wrong her old boyfriend’s declaration, “There are no second acts in American lives.”

Loving Will Shakespeare

Carolyn Meyer

Just before the plague returns to England, seven-year-old Agnes (Anne) Hathaway and her family are invited to a christening by friends: John and Mary Shakespeare, who have just had a son, William. From that point on, Anne’s and Will’s lives will constantly intersect, even when the pair are miles apart.

Despite the title, this appealing novel is not so much the story of Anne and Will’s courtship and marriage as it is of Anne’s coming of age, though the budding playwright is never very far offstage and the love story does assume prominence in the latter part of the book. Growing up as a yeoman farmer’s daughter, Anne, the narrator, is an ordinary girl but by no means a dull one. She must cope with her difficult stepmother and half-sister, the temptations posed by men, the deaths of loved ones, worries over friends who choose to practice Catholicism, and her increasing fear of spinsterhood, and she does so with resourcefulness and good humor. All of this plays out against the vividly rendered backdrop of life in Elizabethan England: the once-in-a-lifetime excitement of a royal progress, the annual May Day and Yuletide feasts, the periodic visitations of plague and sweating sickness, the daily business of running a farm. These elements make this an engrossing story, one that should appeal to adults as well as to the teens for whom it is intended. Ages 12 and up.

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

A Medieval Love Story: Joan of Acre and Ralph de Monthermer

We had a dark post last week, so here's a switch: a medieval love story with a happy ending.

One of the more unlikely romances in the late thirteenth century was that between Joan of Acre, daughter of King Edward I, and Ralph de Monthermer, son of the Lord Knows Who. For Ralph, a squire in Joan's household, was of such obscure origins that his parentage is unknown.

Joan of Acre was born in 1272 in Acre, or Akko, in what is now Israel. Her parents, Eleanor of Castile and the future Edward I, had gone there on crusade. Joan was soon sent to her maternal grandmother in Castile, where she remained until 1278. Her father, now King of England, had plans to marry her to Hartman, son of the King of the Romans, but the young man died in a shipwreck in 1282 before the couple could marry. Undaunted, Edward I soon began searching around for another suitable husband. Soon he lit on one: Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester. Gilbert de Clare, probably the most powerful baron in England at the time and one whose relations with the king had long been stormy. Gilbert had the disadvantage of already having a wife, Alice de Lusignan, but the couple had long been estranged, and in 1285, the marriage was annulled. In 1290, after drawn-out negotiations and the obtaining of a papal dispensation, eighteen-year-old Joan was finally married to forty-six-year-old Gilbert. Before Gilbert's death in December 1295, the couple efficiently produced four children: Gilbert, Eleanor, Margaret, and Elizabeth.

Joan has taken hard knocks at the hands of both historians and novelists. Mary Anne Everett Green in her Lives of the Princesses of England characterizes her as a neglectful mother and a "giddy princess," and other Victorian-era historians, along with many novelists, have acquiesced in this judgment. There seems to be little evidence to support this with regard to her motherhood; though Edward I did arrange for Joan's son Gilbert to live at court when he was seven, this was hardly an atypical arrangement for a noble boy who was also the king's grandson. As for Joan's giddiness, Michael Altschul has commented on the "marked ability" with which Joan controlled the Clare lands after Gilbert's death. There is certainly no evidence that supports the picture of Joan that is painted by romance novelist Virginia Henley, who depicts her as a promiscuous young woman ready to jump into bed with any willing knight.

What can be said about Joan, however, was that she had spirit and willfulness. During her parents' absence in Gascony, when Joan was in her early teens, she became involved in a dispute with the treasurer of her household and refused to accept money from him; her father had to pay her debts when he returned to England. After her marriage, she left court to be alone with her new husband at his manors, to the displeasure of her father, who in reprisal seized seven robes that had been made for her. When her younger brother, the future Edward II, became estranged from Edward I, Joan offered to lend him her seal.

Among the squires in Gilbert de Clare's vast household was one Ralph de Monthermer. Nothing is known of his background, but he soon caught the eye of his widowed mistress, who sent him to her father to be knighted. Sometime at the beginning of 1297, the couple were secretly married.

Edward I, cheerfully ignorant of this match, had meanwhile been searching around for another husband for his daughter, and it is safe to say that Monthermer was not one of the candidates. His words when he heard the rumors about his daughter's attraction to her squire are unrecorded, and in any case are probably best left to the imagination. He seized Joan's estates and formally announced his daughter's betrothal to the Count of Savoy in March 1297. Joan, however, had become "conscious that she was in a situation which would render the disclosure of her marriage inevitable," as Green delicately puts it, and she apparently broke the news of the marriage to her father, who promptly clapped Monthermer into prison at Bristol Castle.

Either before informing her father of her marriage, or after Monthermer had been put into prison--the accounts vary--Joan sent her little daughters to visit their grandfather the king in hopes that they would soften his mood. Evidently, though, more was needed than just the youthful antics of the three Clare sisters. After a great deal of discussion at court about the matter, Joan, as the chronicles report, was at last allowed to plead for herself before her father, at which time she is said to have told the king that as it was no disgrace for an earl to marry a poor woman, it was not blameworthy for a countess to advance a capable young man. This defense is said to have pleased Edward I, though it is probable that Joan's pregnancy, which would have been visible at the time of this exchange in July 1297, also convinced the king to accept the situation. He restored most of Joan's lands to her and pardoned Monthermer, who from November 1297 onward was referred to as the Earl of Gloucester. In the meantime, the couple's first child, named Mary, had been born. She was followed by three others: Thomas, Edward, and Joan.

Ralph soon found himself busy fighting Scots for his new father-in-law, which brought him quickly into favor with the king. In 1301, Edward I restored Tonbridge and Portland to Ralph and Joan in consideration of Ralph's good services in Scotland. Ralph also was on cordial terms with young Prince Edward, who frequently wrote to him. Joan too was friendly with her much younger brother Edward, even offering him her seal when Edward was estranged from his father.

On April 23, 1307, Joan of Acre died. Some Internet sources claim that she died in childbirth--unfortunately, hardly an implausible scenario--but none that I have seen mention a source for this information. Neither Green, Altschul, nor Frances Underwood specify a cause for her death. She was only thirty-five. Ralph was probably not present, being engaged in Scotland at the time. Joan was buried at the priory of Clare in Suffolk. According to Underwood, Osbern Bokenham, a friar there, relayed the odd story that in 1359, Elizabeth de Burgh, Joan's last surviving Clare daughter, inspected her mother's body and found the corpse to be intact. Bokenham also reported that miracles were said to occur at Joan's tomb, including the healing of toothache, back pain, and fever.

Edward I, who ordered that masses be said for his daughter, was himself in poor health; he died in July 1307. Having been styled an earl in right of his wife, Ralph lost his title shortly after her death; Joan and Gilbert de Clare's son, another Gilbert, became the next Earl of Gloucester. The new king, Edward II, granted Ralph five thousand marks for his surrender of the Clare lands to Gilbert, then still a minor. Though his importance had been much diminished, he remained active in Edward II's reign, holding positions such as keeper of the forest south of Trent, and seems to have been neutral or on the king's side during the latter's disputes with his barons. In 1314, he was taken prisoner at Bannockburn but was treated as an honored guest by Robert Bruce, who allowed him to return to England without having to pay a ransom. A story goes that years before, Monthermer, having gotten wind of a plan of Edward I to capture Bruce while he was in London, had sent him coins bearing the king's head and a pair of spurs as a hint that he should slip away. Bruce, having profited from the hint, later remembered this good deed when Monthermer became his prisoner.

Around November 1318, Monthermer made another runaway match, this time to Isabel de Hastings, a widow. Whatever motivated the match, it was an opportune one for Ralph, for Isabel was a member of the Despenser family. Her father, Hugh le Despenser the elder, had long been loyal to Edward II; her brother, Hugh le Despenser the younger, was rapidly becoming Edward II's most trusted advisor (and possibly, his lover). Monthermer, a contemporary of the elder Despenser, was probably at least twenty years older than his new bride. Because the couple had married without the king's license, Isabel's dower lands were seized, but the couple were pardoned the next year in exchange for paying a fine of a thousand marks, which was remitted in 1321.

In 1324, Edward II showed his displeasure with his queen, Isabella, by reducing her household. Among the changes made were that the royal daughters, Eleanor and Joan, were put into Ralph and Isabel's care. Although the timing suggests that Edward II was motivated in part by hostility toward Queen Isabella, it was also typical to give royal children households of their own. The girls and their new guardians stayed at Marlborough Castle.

Ralph died on April 5, 1325, aged sixty-three, and was buried in the Grey Friars' church at Salisbury. The timing of his death was also opportune: it spared him from having to choose whether to remain loyal to Edward II or to support Queen Isabella and Roger Mortimer, who overthrew the king in 1326. Ralph's connection with the Despenser family might have been a fatal one had he elected to side with the king. The king and queen's daughters remained with the widowed Isabel until October 1326, when Queen Isabella was reunited with them at Bristol Castle, where they and Hugh le Despenser the elder were staying. Isabel was presumably at the castle with her charges and may have had the misfortune of seeing her father's surrender to Isabella and Mortimer and his execution the following day. Her brother was executed less than a month later.

Isabel herself does not seem to have been punished by the new rulers, although in June 1328, she acknowledged a debt of nearly three hundred pounds to Queen Isabella. Whether this was a real debt stemming out of her care of the queen's children or whether she was forced to make the acknowledgment to avoid the wrath of the queen's regime is unknown.

Ralph and Isabel had apparently had no surviving children. Ralph's two sons by Joan of Acre, Thomas and Edward, were on good enough terms with the new regime to be knighted in 1327, but Thomas later joined Henry, Earl of Lancaster's rebellion against Queen Isabella and Mortimer, while Edward became entangled with the Earl of Kent, Edward II's half-brother, who had plotted to release Edward II, whom he believed to be still alive, from captivity. The earl, who had likely been entrapped into the plot by Queen Isabella and Mortimer, was beheaded in 1330 for his fraternal loyalty, but Edward de Monthermer got off more lightly, being imprisoned in Winchester Castle at the crown's expense. Fortunately for Edward, Mortimer's days were numbered; he was seized by Edward III in October 1330 and hanged the following month. Edward de Monthermer's lands were restored to him in December 1330. Thomas, who had been fined for his role in Lancaster's rebellion, had his fine remitted in January 1331.

Edward de Monthermer, who had taken part in Edward III's wars but who had fallen ill, came to live with his half-sister Elizabeth de Burgh in 1339 and died before February 1340. He was buried near Joan of Acre; Elizabeth de Burgh, who took charge of his funeral, had his tomb made. Ralph and Joan's younger daughter, Joan, became a nun at Amesbury; their older daughter, Mary, wed the Earl of Fife. Thomas de Monthermer married Margaret, the widow of Henry Teyes, and died in 1340 at the sea battle of Sluys. His daughter, Margaret, married John de Montacute, the younger son of William de Montacute, Earl of Salisbury. John and Margaret's son, John, later succeeded to the earldom of Salisbury. From him would descend Warwick the Kingmaker and his daughter Anne, queen to Richard III. It was an impressive lineage for Ralph de Monthermer, the obscure squire who had married a princess.

One of the more unlikely romances in the late thirteenth century was that between Joan of Acre, daughter of King Edward I, and Ralph de Monthermer, son of the Lord Knows Who. For Ralph, a squire in Joan's household, was of such obscure origins that his parentage is unknown.

Joan of Acre was born in 1272 in Acre, or Akko, in what is now Israel. Her parents, Eleanor of Castile and the future Edward I, had gone there on crusade. Joan was soon sent to her maternal grandmother in Castile, where she remained until 1278. Her father, now King of England, had plans to marry her to Hartman, son of the King of the Romans, but the young man died in a shipwreck in 1282 before the couple could marry. Undaunted, Edward I soon began searching around for another suitable husband. Soon he lit on one: Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester. Gilbert de Clare, probably the most powerful baron in England at the time and one whose relations with the king had long been stormy. Gilbert had the disadvantage of already having a wife, Alice de Lusignan, but the couple had long been estranged, and in 1285, the marriage was annulled. In 1290, after drawn-out negotiations and the obtaining of a papal dispensation, eighteen-year-old Joan was finally married to forty-six-year-old Gilbert. Before Gilbert's death in December 1295, the couple efficiently produced four children: Gilbert, Eleanor, Margaret, and Elizabeth.

Joan has taken hard knocks at the hands of both historians and novelists. Mary Anne Everett Green in her Lives of the Princesses of England characterizes her as a neglectful mother and a "giddy princess," and other Victorian-era historians, along with many novelists, have acquiesced in this judgment. There seems to be little evidence to support this with regard to her motherhood; though Edward I did arrange for Joan's son Gilbert to live at court when he was seven, this was hardly an atypical arrangement for a noble boy who was also the king's grandson. As for Joan's giddiness, Michael Altschul has commented on the "marked ability" with which Joan controlled the Clare lands after Gilbert's death. There is certainly no evidence that supports the picture of Joan that is painted by romance novelist Virginia Henley, who depicts her as a promiscuous young woman ready to jump into bed with any willing knight.

What can be said about Joan, however, was that she had spirit and willfulness. During her parents' absence in Gascony, when Joan was in her early teens, she became involved in a dispute with the treasurer of her household and refused to accept money from him; her father had to pay her debts when he returned to England. After her marriage, she left court to be alone with her new husband at his manors, to the displeasure of her father, who in reprisal seized seven robes that had been made for her. When her younger brother, the future Edward II, became estranged from Edward I, Joan offered to lend him her seal.

Among the squires in Gilbert de Clare's vast household was one Ralph de Monthermer. Nothing is known of his background, but he soon caught the eye of his widowed mistress, who sent him to her father to be knighted. Sometime at the beginning of 1297, the couple were secretly married.

Edward I, cheerfully ignorant of this match, had meanwhile been searching around for another husband for his daughter, and it is safe to say that Monthermer was not one of the candidates. His words when he heard the rumors about his daughter's attraction to her squire are unrecorded, and in any case are probably best left to the imagination. He seized Joan's estates and formally announced his daughter's betrothal to the Count of Savoy in March 1297. Joan, however, had become "conscious that she was in a situation which would render the disclosure of her marriage inevitable," as Green delicately puts it, and she apparently broke the news of the marriage to her father, who promptly clapped Monthermer into prison at Bristol Castle.

Either before informing her father of her marriage, or after Monthermer had been put into prison--the accounts vary--Joan sent her little daughters to visit their grandfather the king in hopes that they would soften his mood. Evidently, though, more was needed than just the youthful antics of the three Clare sisters. After a great deal of discussion at court about the matter, Joan, as the chronicles report, was at last allowed to plead for herself before her father, at which time she is said to have told the king that as it was no disgrace for an earl to marry a poor woman, it was not blameworthy for a countess to advance a capable young man. This defense is said to have pleased Edward I, though it is probable that Joan's pregnancy, which would have been visible at the time of this exchange in July 1297, also convinced the king to accept the situation. He restored most of Joan's lands to her and pardoned Monthermer, who from November 1297 onward was referred to as the Earl of Gloucester. In the meantime, the couple's first child, named Mary, had been born. She was followed by three others: Thomas, Edward, and Joan.

Ralph soon found himself busy fighting Scots for his new father-in-law, which brought him quickly into favor with the king. In 1301, Edward I restored Tonbridge and Portland to Ralph and Joan in consideration of Ralph's good services in Scotland. Ralph also was on cordial terms with young Prince Edward, who frequently wrote to him. Joan too was friendly with her much younger brother Edward, even offering him her seal when Edward was estranged from his father.

On April 23, 1307, Joan of Acre died. Some Internet sources claim that she died in childbirth--unfortunately, hardly an implausible scenario--but none that I have seen mention a source for this information. Neither Green, Altschul, nor Frances Underwood specify a cause for her death. She was only thirty-five. Ralph was probably not present, being engaged in Scotland at the time. Joan was buried at the priory of Clare in Suffolk. According to Underwood, Osbern Bokenham, a friar there, relayed the odd story that in 1359, Elizabeth de Burgh, Joan's last surviving Clare daughter, inspected her mother's body and found the corpse to be intact. Bokenham also reported that miracles were said to occur at Joan's tomb, including the healing of toothache, back pain, and fever.

Edward I, who ordered that masses be said for his daughter, was himself in poor health; he died in July 1307. Having been styled an earl in right of his wife, Ralph lost his title shortly after her death; Joan and Gilbert de Clare's son, another Gilbert, became the next Earl of Gloucester. The new king, Edward II, granted Ralph five thousand marks for his surrender of the Clare lands to Gilbert, then still a minor. Though his importance had been much diminished, he remained active in Edward II's reign, holding positions such as keeper of the forest south of Trent, and seems to have been neutral or on the king's side during the latter's disputes with his barons. In 1314, he was taken prisoner at Bannockburn but was treated as an honored guest by Robert Bruce, who allowed him to return to England without having to pay a ransom. A story goes that years before, Monthermer, having gotten wind of a plan of Edward I to capture Bruce while he was in London, had sent him coins bearing the king's head and a pair of spurs as a hint that he should slip away. Bruce, having profited from the hint, later remembered this good deed when Monthermer became his prisoner.

Around November 1318, Monthermer made another runaway match, this time to Isabel de Hastings, a widow. Whatever motivated the match, it was an opportune one for Ralph, for Isabel was a member of the Despenser family. Her father, Hugh le Despenser the elder, had long been loyal to Edward II; her brother, Hugh le Despenser the younger, was rapidly becoming Edward II's most trusted advisor (and possibly, his lover). Monthermer, a contemporary of the elder Despenser, was probably at least twenty years older than his new bride. Because the couple had married without the king's license, Isabel's dower lands were seized, but the couple were pardoned the next year in exchange for paying a fine of a thousand marks, which was remitted in 1321.

In 1324, Edward II showed his displeasure with his queen, Isabella, by reducing her household. Among the changes made were that the royal daughters, Eleanor and Joan, were put into Ralph and Isabel's care. Although the timing suggests that Edward II was motivated in part by hostility toward Queen Isabella, it was also typical to give royal children households of their own. The girls and their new guardians stayed at Marlborough Castle.

Ralph died on April 5, 1325, aged sixty-three, and was buried in the Grey Friars' church at Salisbury. The timing of his death was also opportune: it spared him from having to choose whether to remain loyal to Edward II or to support Queen Isabella and Roger Mortimer, who overthrew the king in 1326. Ralph's connection with the Despenser family might have been a fatal one had he elected to side with the king. The king and queen's daughters remained with the widowed Isabel until October 1326, when Queen Isabella was reunited with them at Bristol Castle, where they and Hugh le Despenser the elder were staying. Isabel was presumably at the castle with her charges and may have had the misfortune of seeing her father's surrender to Isabella and Mortimer and his execution the following day. Her brother was executed less than a month later.

Isabel herself does not seem to have been punished by the new rulers, although in June 1328, she acknowledged a debt of nearly three hundred pounds to Queen Isabella. Whether this was a real debt stemming out of her care of the queen's children or whether she was forced to make the acknowledgment to avoid the wrath of the queen's regime is unknown.

Ralph and Isabel had apparently had no surviving children. Ralph's two sons by Joan of Acre, Thomas and Edward, were on good enough terms with the new regime to be knighted in 1327, but Thomas later joined Henry, Earl of Lancaster's rebellion against Queen Isabella and Mortimer, while Edward became entangled with the Earl of Kent, Edward II's half-brother, who had plotted to release Edward II, whom he believed to be still alive, from captivity. The earl, who had likely been entrapped into the plot by Queen Isabella and Mortimer, was beheaded in 1330 for his fraternal loyalty, but Edward de Monthermer got off more lightly, being imprisoned in Winchester Castle at the crown's expense. Fortunately for Edward, Mortimer's days were numbered; he was seized by Edward III in October 1330 and hanged the following month. Edward de Monthermer's lands were restored to him in December 1330. Thomas, who had been fined for his role in Lancaster's rebellion, had his fine remitted in January 1331.

Edward de Monthermer, who had taken part in Edward III's wars but who had fallen ill, came to live with his half-sister Elizabeth de Burgh in 1339 and died before February 1340. He was buried near Joan of Acre; Elizabeth de Burgh, who took charge of his funeral, had his tomb made. Ralph and Joan's younger daughter, Joan, became a nun at Amesbury; their older daughter, Mary, wed the Earl of Fife. Thomas de Monthermer married Margaret, the widow of Henry Teyes, and died in 1340 at the sea battle of Sluys. His daughter, Margaret, married John de Montacute, the younger son of William de Montacute, Earl of Salisbury. John and Margaret's son, John, later succeeded to the earldom of Salisbury. From him would descend Warwick the Kingmaker and his daughter Anne, queen to Richard III. It was an impressive lineage for Ralph de Monthermer, the obscure squire who had married a princess.

Friday, November 24, 2006

680 Years Ago Today in Hereford

Today is the 680th anniversary of the death of Hugh le Despenser the younger. I'm too lazy to write a proper blog entry about it. Instead, here's the scene as I wrote it in The Traitor's Wife. (It's not dinnertime fare.)

Leybourne and Stanegrave and their men had made Hugh’s journey to Hereford as miserable as Isabella and Mortimer could have wished. Lest any dozing village miss the fine sight of Hugh le Despenser chained to a mangy horse, a drummer and a trumpeter had been put at the head of the procession to announce his arrival well in advance. This was the cue for villagers to throw anything they could find at Hugh, and at Simon de Reading as well. Hardly anyone knew who the latter was, of course, but as he too was in chains, everyone realized that he had to be associated with Hugh, and his presence made the proceedings twice as fun and provided some consolation for those whose aim was too unsure to hit Hugh himself.

But the true festivities started when the troops, trailed by an ever-increasing crowd of citizens eager to see Hugh hang, reached the outskirts of Hereford, where they were met by a contingent of the queen’s men coming from the city, led by Jean de Hainault and Thomas Wake. There, to the delight of the crowd, Hugh and Simon were dragged off their horses and stripped naked, then redressed in tunics bearing their coats of arms reversed. With the help of a clerk, whose Latin was needed for the purpose, the words from the Magnificat “He has put down the mighty from their seat and hath exalted the humble” were etched into Hugh’s bare shoulders. His chest bore psalm verses beginning, “Why dost thou glory in malice, thou that art mighty in iniquity?” Thus decorated, and wearing a crown of nettles, he was put back on his horse. Then, to the blare of trumpets and drums, accompanied by the howling of the spectators, he was led into the city with Simon de Reading forced to march in front of him bearing his standard reversed. As there were only so many horse droppings that could be found to throw at the captives, the enterprising were selling eggs for that purpose.

Zouche had hoped to miss these proceedings. He had retrieved the records, and the little treasure that could be found, from Swansea, and had delivered his load to the queen two days before. But having made good time to Hereford, he could not leave once the execution had been scheduled. Thus, he was standing in the market square, near the queen, Mortimer, and the Duke of Aquitaine [the future Edward III], when Hugh and Simon, so covered in filth that they resembled scarecrows more than men, were brought there for trial.

Isabella, still clad in widow’s weeds, wore a look of resignation as William Trussell stepped forth to read the charges against Hugh. Only Mortimer, making no attempt to hide his own satisfaction, saw the sparkle in her eyes.

***

At what passed for his trial, Hugh’s mind wandered from the past to the present, sometimes lucidly, sometimes not. There were many charges against him, some true enough, some with a bit of truth to them, some so patently absurd that it was a wonder Trussell could keep a straight face. Piracy. Returning to England after his banishment. Procuring the death of the saintly Lancaster after imprisoning him on false charges. Executing other men who had fought against the king at Boroughbridge on false charges. Forcing the king to fight the Scots. Abandoning the queen at Tynemouth. (That again, Hugh thought.) Making war on the Christian Church. Disinheriting the king by inducing him to grant the earldom of Winchester to his father and the earldom of Carlisle to Harclay. Bribing persons in France to murder the queen and her son… He drifted off into a world where his death was not imminent, and when he was shaken back to the here and now once more, Trussell was still going on, perhaps beginning to bore those assembled a little. Trussell himself must have sensed this, for he sped through the last few charges (leading the king out of his realm to his dishonor and taking with him the treasure of the kingdom and the Great Seal) before he slowed his voice dramatically for what all were anticipating: his sentence. Though no one could have possibly been surprised by it, least of all Hugh himself, there were nonetheless appreciative gasps as Trussell, all but smacking his lips, informed Hugh what was to be done with him.

“Hugh, you have been judged a traitor since you have threatened all the good people of the realm, great and small, rich and poor, and by common assent you are also a thief. As a thief you will hang, and as a traitor you will be drawn and quartered, and your quarters will be sent throughout the realm. And because you prevailed upon our lord the king, and by common assent you returned to the court without warrant, you will be beheaded. And because you were always disloyal and procured discord between our lord the king and our very honorable lady the queen, and between other people of the realm, you will be disemboweled, and then your entrails will be burnt. Go to meet your fate, traitor, tyrant, renegade. Go to receive your own justice, traitor, evil man, criminal!”

***

At Hereford Castle, to which Hugh was dragged by four horses, a gallows fifty feet high had been erected. “Just for you!” said one of the men who untied him from his hurdle and hauled him toward the gallows. “Ain’t we the special one, now?”